blog

UNSW COMP6771 (Advanced C++) Week 5 Operator Overloading

Smart Pointer

Object lifetimes

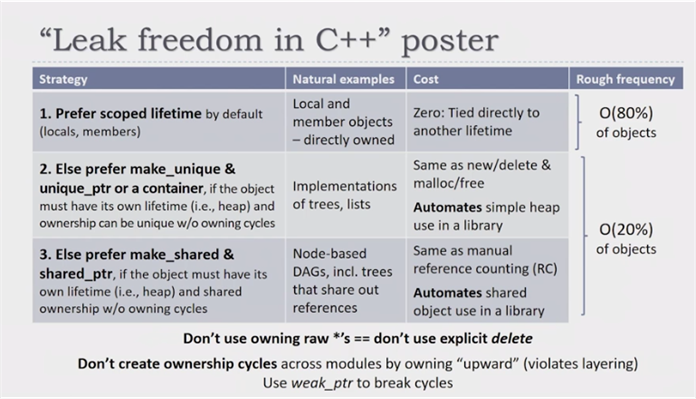

To create safe object lifetimes in C++, we always attach the lifetime of one object to that of something else

- Named objects:

- A variable in a function is tied to its scope

- A data member is tied to the lifetime of the class instance

- An element in a std::vector is tied to the lifetime of the vector

- Unnamed objects:

- A heap object should be tied to the lifetime of whatever object created it

- Examples of bad programming practice

- An owning raw pointer is tied to nothing

- A C-style array is tied to nothing

If new keyword is used, it should be manually delete‘d, like malloc and free in C. Raw pointers should be avoided in C++.

std::unique_pointer<T>

Owns the object, the underlying object will be destructed when the pointer is destructed. std::experimental::observer_ptr<T> does not have ownership of the pointer, and can be used to observe a unique pointer, but it must ensure it does not access the data after the original pointer is destructed.

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

std::unique_ptr<int> up1{new int};

std::unique_ptr<int> up2 = up1; // no copy constructor

std::unique_ptr<int> up3;

up3 = up2; // no copy assignment

up3.reset(up1.release()); // OK

std::unique_ptr<int> up4 = std::move(up3); // OK

std::cout << up4.get() << "\n";

std::cout << *up4 << "\n";

std::cout << *up1 << "\n";

}

Unique pointer has no copy cnostructor nor copy assignment. To transfer ownership, use .reset and .release or std::move.

#include <memory>

#include <experimental/memory>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

int *i = new int;

std::unique_ptr<int> up1{i};

*up1 = 5;

std::cout << *up1 << "\n";

std::experimental::observer_ptr<int> op1{i};

*op1 = 6;

std::cout << *op1 << "\n";

up1.reset();

std::cout << *op1 << "\n";

}

Usage of observer pointer

#include <memory>

#include <experimental/memory>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

// 1 - Worst

int *i = new int;

std::unique_ptr<std::string> up1{i};

// 2 - Not good

std::unique_ptr<std::string> up2{new std::string{"Hello"}};

// 3 - Good

std::unique_ptr<std::string> up3 = make_unique<std::string>("Hello");

std::cout << *up3 << "\n";

std::cout << *(up3.get()) << "\n";

std::cout << up3->size();

}

To remove keyword new completely, use make_unique, a wrapper of new.

std::shared_pointer<T>

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

std::shared_ptr<int> x = std::make_shared<int>(5);

std::shared_ptr<int> y = x; // Both now own the memory

std::cout << "use count: " << x.use_count() << "\n";

std::cout << "value: " << *x << "\n";

x.reset(); // Memory still exists, due to y.

std::cout << "use count: " << y.use_count() << "\n";

std::cout << "value: " << *y << "\n";

y.reset(); // Deletes the memory, since

// no one else owns the memory

std::cout << "use count: " << x.use_count() << "\n";

std::cout << "value: " << *y << "\n";

}

There is a reference count of the pointer. It will be destructed only if all the shared pointers goes out of scope (count becomes 0). It may have many observers, but they still do not get ownership.

std::weak_ptr

#include <memory>

#include <iostream>

int main() {

std::shared_ptr<int> x = std::make_shared<int>(1);

std::weak_ptr<int> wp = x; // x owns the memory

{

std::shared_ptr<int> y = wp.lock(); // x and y own the memory

if (y) {

// Do something with y

std::cout << "Attempt 1: " << *y << '\n';

}

} // y is destroyed. Memory is owned by x

x.reset(); // Memory is deleted

std::shared_ptr<int> z = wp.lock(); // Memory gone; get null ptr

if (z) {

// will not execute this

std::cout << "Attempt 2: " << *z << '\n';

}

}

It does not add reference count initially, but .lock() returns a shared pointer which has reference incremented. Before accessing underlying data of a weak poiner, must check if it is still valid.

Which one to use

- use shared pointer if either

- You have several pointers, and you don’t know which one will stay around the longest

- You need temporary ownership (outside scope of this course)

- else use unique pointer

Exceptions

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

int main() {

std::cout << "Enter -1 to quit\n";

std::vector<int> items{97, 84, 72, 65};

std::cout << "Enter an index: ";

for (int print_index; std::cin >> print_index; ) {

if (print_index == -1) break;

try {

std::cout << items.at(print_index) << '\n';

items.resize(items.size() + 10);

} catch (const std::out_of_range& e) {

std::cout << "Index out of bounds\n";

} catch (...) {

std::cout << "Something else happened";

}

std::cout << "Enter an index: ";

}

}

- Exceptions are exceptional circumstances, which differs from bug. It happens during run-time anomalies.

- Exception handling is a run-time mechanism, which allows us to gracefully and programmatically deal with anomalies, as opposed to our program crashing.

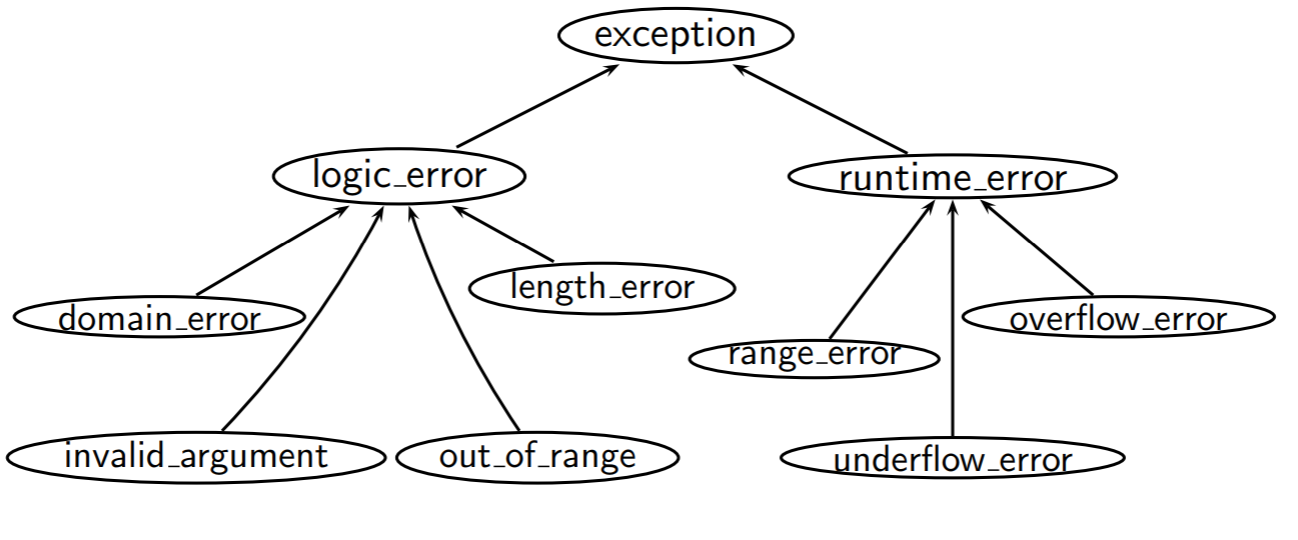

Exception Objects

Any type derived from std::exception, customised exceptions can inherit from these types. Standard exceptions are defined in <stdexcept>.

<stdexcept>defines a set of standard exceptions that both the library and programs can use to report common errors.<exception>defines the base class (i.e., std::exception) for all exceptions thrown by the elements of the standard library, along with several types and utilities to assist handling exceptions.

Catching the right way

Throw by value, catch by const reference.

Catch by value is inefficient

#include <iostream>

class Giraffe {

public:

Giraffe() { std::cout << "Giraffe constructed" << '\n'; }

Giraffe(const Giraffe &g) { std::cout << "Giraffe copy-constructed" << '\n'; }

~Giraffe() { std::cout << "Giraffe destructed" << '\n'; }

};

void zebra() {

throw Giraffe{};

}

void llama() {

try {

zebra();

} catch (Giraffe g) {

std::cout << "caught in llama; rethrow" << '\n';

throw;

}

}

int main() {

try {

llama();

} catch (Giraffe g) {

std::cout << "caught in main" << '\n';

}

}

Catch by reference is more efficient

#include <iostream>

class Giraffe {

public:

Giraffe() { std::cout << "Giraffe constructed" << '\n'; }

Giraffe(const Giraffe &g) { std::cout << "Giraffe copy-constructed" << '\n'; }

~Giraffe() { std::cout << "Giraffe destructed" << '\n'; }

};

void zebra() {

throw Giraffe{};

}

void llama() {

try {

zebra();

} catch (const Giraffe& g) {

std::cout << "caught in llama; rethrow" << '\n';

throw;

}

}

int main() {

try {

llama();

} catch (const Giraffe& g) {

std::cout << "caught in main" << '\n';

}

}

Rethrow

try {

try {

try {

throw T{};

} catch (T& e1) {

std::cout << "Caught\n";

throw;

}

} catch (T& e2) {

std::cout << "Caught too!\n";

throw;

}

} catch (...) {

std::cout << "Caught too!!\n";

}

Exceptions can be rethrew after catching.